Mocking up my portable sharpening station. I want my sharpening stones and strop to be laid out ready to use wherever I am. The folded-back cardboard is to figure out the articulated lid.

I bought my first 10-speed bike over 30 years ago, when I lived in Houston, TX. It was a cheap, basic Sears bike. The derailleur for shifting gears was a decades-old design, with frame-mounted levers. I rode it along the paved Braes Bayou trail, which over its 5-mile distance probably had at most a 10-foot rise.

Shifting gears on the bike was a nuisance, because there was no way to know other than the sound of the chain when I had the shift lever in the right position, plus I had to lean down to reach the levers. So I'd be leaning over off-balance hunting back and forth to find the gear. Because of this and the flat terrain, I basically treated it as a 3-speed: starting, accelerating, and cruising. Once up to speed, I didn't change gears.

Five years later, living in hillier Dallas, I upgraded to a much nicer bike, six times the price. This had 12 speeds, but was still the same basic shifter design. New indexed shifting systems were just coming on the market at the time, along with step-in pedals, but were expensive. The terrain required me to shift more, but I was still young enough that I could just power through a limited range of gears.

By the time I bought my third bike fifteen years after that, I was living in Massachusetts, with much more varied terrain. By now we were up to 21 speeds (7-speed hub by 3-speed chain ring), and 12 times the cost of my first bike. Indexed shifting was standard equipment, with the shifters built into the brake levers. That meant I never had to remove my hands from the handlebars. Tap a brake lever sideways, and click! it shifts, the gear falling smoothly into place. No messing about trying to find the gear.

This was a major mechanical innovation in shifting systems, and completely changed the way I rode. The terrain dictated frequent shifting, and because it was easy to do, I shifted frequently. Click! Click-click! Constantly adjusting to the road. Think of driving a manual transmission car in city traffic. You constantly have to down shift after stopping, shift through a couple gears as you speed up, down shift again after hitting the brakes. You don't stay in two gears the whole time. That would put a huge load on the engine and transmission, causing failure.

Cycling is much the same, except that your legs are the engine. Hard pedaling is, well, hard! Too much of it takes the fun out. But with a good variable speed transmission that's easy to shift, you can keep pedaling at the same cadence and load no matter what. That opens up a whole new world of cycling, making it more enjoyable (especially when you've gotten old enough for enjoyment to take priority over machismo).

The point is, when it's easy to do, you'll do it more often, and enjoy the benefits of that increased frequency. In hand tools, sharpening is like that. When it's inconvenient, you put it off, and suffer as a result. For me it was inconvenient because I had to pull my stones out of a drawer, set them out on the bench, open up the cases, then put them away after use, as well as deal with the mess (sharpening is messy any way you do it). Too much interruption to my work.

I wanted to have a way to keep my sharpening stones accessible at all times, so at any moment I could step away from my work to take 30 seconds and sharpen a tool. A dedicated sharpening station is the obvious solution, but I also wanted to be able to do the same thing if I was off doing a demo or class somewhere.

My solution is a portable sharpening station with a cover that allows me to open it up and go right to work, with the stones laid out and ready, yet secure in position. It also helps contain the mess. I use Norton 3" wide oilstones, but this will also work with their 3" waterstones. You can do the same thing with other brands of oil, water, or diamond stones. They don't even have to be the same size, though that makes layout easier (my Norton translucent Arkansas stone turned out to be 1/16" longer than my coarse India stone). I also made a matching strop to go in the set.

The design is roughly like a briefcase with fitted dividers and sections, and an articulated lid that folds back. The body is 1/2" and 1/4" baltic birch plywood panels with oak banding; the dividers are all oak. The banding is raised around the bottom to form a 1/4" basin. The stones sit in this, with 1/4" thick by 3/4" wide spacers separating them.

In addition to the fitted bench stone holders, it has a fitted box to hold a set of very nice Chris Pye carving slip stones that I got recently from Tools For Working Wood, and a larger box for holding oil, strop compound, file and burnisher for sharpening scrapers, and small clamps for clamping the station to a surface. The finish is heavy duty "spar varnish" outdoor grade polyurethane, to resist the sharpening residue.

The dividers and boxes start making for some tight tolerances. Because they are small and thin, you have to be careful forming them. One half-stroke extra on the saw can ruin the appearance of a joint (though it should still be fine structurally). Fortunately, a little sawdust and glue pressed into any little imperfections cleans them up, especially in the busy open-grained oak. But in general, I give credit to Paul Sellers' Working Wood series for the tight joints and hinge mortises I was able to get.

Crosscutting a piece of 1/2" plywood for the bottom panel. I scored the cut line with a knife to avoid tearing of the outer ply.

Ripping off the excess.

Once the plywood was cut to size, I worked on the oak banding and interior parts. The bottom banding is 3/4" square cross section, with a 1/2" x 1/4" rabbet for the plywood. The dividers that form the interior boxes are 1/4" and 3/8" thick oak, which I got by resawing 3/4" stock.

Ripping down a 3/4" width of oak for the banding.

Edge jointing a section of the banding to final dimension.

My fillister plane needed a minor repair first: gluing the boxing back in place.

Ripping a section of oak for the interior dividers.

Resawing the divider stock to get a 1/4" thickness.

With the glue on the plane boxing dry, molding the rabbet in the banding. I need to make a sticking board for this.

Precision tuning of the rabbet with a small shoulder plane. Any humps or crud in the corner will prevent a good fit around the plywood edge.

Using my Tite-Mark as a thickness gauge to check the rabbet.

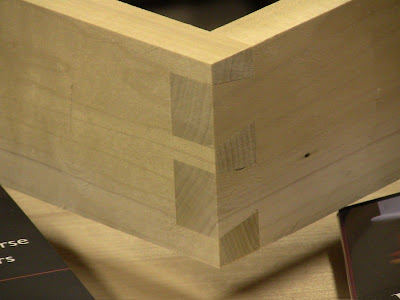

Closeup of the joint at the rear corner. On the left is the back piece, rabbeted to be the rear edge of the banding over the plywood. On the right is a side piece, rabbeted and notched to fit into the back piece.

With back and banding dry fitted, marking the main divider to fit.

Shooting the divider for a precise fit.

Another piece of the same stock, showing how to test for a well-shot board: if it can stand on end and stay standing when you bang on the bench, the end is dead flat and square.

With a couple of oilstones in place, fitting the position of the divider. After taking this photo, I decided to add a flat spacer between the stones and the divider. You'll see the reason for that in part 2. This also threw off the measurements in my layout sketch a bit.

The divider is the long side of an interior box. Here's one of the short-side pieces in 3/8" stock, dadoed into the back without glue. Paul Sellers says a dado should fit snug enough that you can lift the board without the crosspiece coming out.

Ripping off a 1/4" thick piece of 3/4" stock. This will be a flat spacer between stones.

Planing the surface of the 1/4" stock. Holding this thin stuff is a bit of a challenge. I had to plane it in sections, moving the holdfast around.

A brief diversion. My wife had asked me to repair the support leg on the back of an antique picture frame for a friend. The backing board is heavy fiberboard covered with velvet on one side and some kind of liner paper on the other. The leg is the same construction, hinged at the top with cloth. At some point, the frame got knocked down flat, bending the leg so that it fractured in the middle, flopping about and no longer supporting the frame.

My vague plan for repair was to glue slips of wood into the leg. I needed some more 1/4" oak divider stock, so rather than planing the remainder from the first resaw down to thickness, I decided to see if I could resaw it again and save the thin cutoff layer for the picture frame. Time to pull out my ryoba (with hardwood tooth pattern).

This is ridiculously thin resawing, but the ryoba handled it well.

Success! That's a useful skill to have.

After trimming the ultra-thin oak to shape, I glued it in between the layers of fiberboard and lining paper. That should last a hundred years. You can see the picture frame back face down on the bench-on-bench, with its bent support leg.

Back to the project. I glued up the interior box corners in multiple subassembly stages. This all goes together as a bit of a puzzle, so it's impossible to do as a single glue-up. That also allowed me to plane the dovetails flush once they were dry.

Dry fit. Except for the leftmost dado here, all the small dado and dovetail joints on the interior box and dividers are snug enough to be self-supporting without glue.

Glue-up detail of the corner of the small box: using a tiny caul to pull the dovetail in tight. I made it by chiseling a small depression in a bit of scrap pine.

Glue-up of the banding and the box assembly. I installed the hinges before gluing up the box.

To ensure good bonding of the back to the plywood, I put a caul on the underside and clamped it in place. I added two more clamps to those shown here to apply even pressure.

While the glue was drying, I made the dividers for the Chris Pye slip stones. These stones are 3" squares in several thicknesses, in coarse India and hard Arkansas, with different curve profiles one each edge. The dividers are made up from thin resawn pine, covered with a continuous layer of felt in sort of an accordion fashion.

I told you thin resawing was a good skill to have! Here's a piece of 3/4" pine resawn into 5 layers. I planed them smooth by holding down one end at a time with a holdfast.

That thing next to the plane? From Jim Kingshott's books and videos, an oil wick, made of felt rolled into a small plastic spice jar fitted into a base with sandpaper on the bottom. Just put a dab of linseed oil on the wick, then pull the plane over it on the return stroke whenever you need to lubricate the bottom. This is faster than stopping to rub wax on it. Also good for passing a saw blade across on each side. I keep it in an old tea tin to limit its oxygen supply. Linseed oil-soaked rags are notorious for starting shop fires by spontaneous combustion.

The felt-covered dividers glued-up, with spacing custom-fitted to the stones. A layer of wax paper keeps the glue off the stones.

After the glue has dried. You can see how strips of felt have been glued to the wood in a continuous fashion. This drops into the small box, no need to glue the sides in place.

Once I removed the main base from the clamps, I fitted up the bench stone spacers. Using my long shooting board, I trimmed them in succession to width until everything dropped into the main base snugly.

Test fit of the bench stones and their spacers, and the slip stones in their dividers. I was a little too tight on clearances: I had to shave off the outer layers of felt with a chisel to make the slips move smoothly.

The photo above reveals another clearance problem. Remember I said I had thrown off the measurements in my layout sketch when I moved the long divider back? Notice how the hinge rests on the corner of the slip stones. That wasn't supposed to happen. My goal in all this was to have the hinge on the top side of the case, not the back, so that when the case was standing up on its back, it would sit flat on the floor, no hinge spines in the way.

How I had drawn it up: the hinge would attach to the outside of the edge banding for the lid, which would clear the slip stone box as it pivoted up. But now as you can see the box is in the way.

New plan: rather than having the hinge close down all the way, have it close down to the quarter-open position. It will attach to the underside of the banding, leaving plenty of clearance. That means there will be a ledge at the back when the lid is closed down. Not ideal, but I can live with it.

The lid rear banding molded and mortised for the hinges. Notice how it is not flush with the back: that's because it's mortised deeply...

... so that when the lid is down, it leaves a minimal gap at the hinge line. Note the ledge formed by the banding and the back.

There are various ways I could have dealt with the hinge, but with it already secured to the back, this was simple and effective, if not the prettiest. Design changes midway through construction are bound to cause problems later! That's why you do mockups and prototypes and stare at them for a while before making any decisions. However, since this is shop furniture, I just need it to be functional.

Next will be building the articulated lid.

(Continue to part 2)